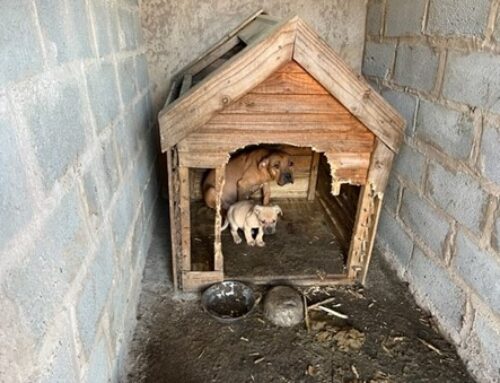

As social media platforms continue to evolve, especially with the rapid rise in the popularity of TikTok in South Africa, the National Council of SPCAs (NSPCA) has become increasingly concerned with the alarming surge in content depicting animal cruelty being shared online. This disturbing trend is not only unprecedented but has led to a significant shift in the NSPCA’s priorities, prompting more resources to be directed toward investigating “social media crimes” and less time spent on traditional fieldwork, including vital on-the-ground inspections and investigations.

The nature of these videos presents significant challenges, particularly due to the scarcity of crucial information, such as the incident’s date, time, and location. Additionally, identifying those responsible for both committing these heinous acts and distributing the content remains a difficult task.

The NSPCA reported on two incidents of severe, deliberate animal cruelty captured on video and shared online in the last quarter of 2024. In January 2025 alone, five of these tragic incidents were reported. These acts include the brutal killing of a warthog;[1] the cruel stoning of a brown hyena;[2] the conviction of a man who smoked marijuana through a container containing a live snake;[3] a TikTok influencer who force-fed a fish with beer;[4] a Nile crocodile who was kicked, beaten, and had its teeth slashed out;[5] a male Chacma baboon who was chased, beaten, and set alight at a school in Delmas, Mpumalanga;[6] and most recently a Zebra, who was hacked to death with an axe while still alive.[7]

This surge in cruelty has led the NSPCA to question the motivations behind this phenomenon. On one hand, what drives social media users to engage in or support such acts of animal cruelty, while simultaneously sharing the content online? On the other, what explains the consumers’ insatiable appetite for such material, leading it to go viral – often due to widespread outrage and dissent rather than its merit?

This article aims to explore the psychology of the consumption of animal cruelty content on social media and the psychological effects thereof.

Types of Social Media “Publishers”

In all seven incidents of deliberate animal cruelty caught on video and circulated on social media mentioned above, the publishers who caused such content to go viral can be divided into four distinct categories, namely:

- Influencers who commit animal cruelty for entertainment;

- Those who participate in groups committing animal cruelty, even without directly inflicting harm;

- Bystanders who film an unaffiliated party not and do not intervene; and

- Those who share existing footage of animal cruelty, despite not being present during the act.

Influencers Committing Cruelty for Entertainment

This category of conduct is not new and has manifested itself on YouTube at least twice in the past. However, platforms such as TikTok and those who have adopted short-form video content features (e.g. Instagram reels, YouTube shorts) make it easier to generate accessible content. influencers may feel compelled to post sensationalist content with “shock value” to maintain popularity and influence.

Individuals in this category often engage in animal cruelty to gain attention, increase their online following, and achieve financial gain. The desire for social recognition and monetary rewards can drive them to create provocative content, regardless of ethical considerations. This behaviour aligns with findings that unethical treatment of animals is sometimes employed to generate fame and profit on social media platforms.[8]

Participants to Group Animal Cruelty

An example of this category is the Zebra incident,[9] where the dialogue between the participants and their close proximity to the incident make it clear that the perpetrators know each other, are familiar, and act with a common purpose in the execution of the animal cruelty.

Those who participate in groups committing animal cruelty, even without directly inflicting harm, may be influenced by social dynamics such as peer pressure and a desire for group acceptance. The collective environment can diminish personal accountability, leading individuals to partake in or support actions they might otherwise avoid.

Non-intervening Bystanders

As can be seen in the footage of the Chacma baboon,[10] these obscene acts of animal cruelty sometimes attract a crowd, who film the incidents and share them on social media, without intervening in the cruelty, thereby allowing it to continue.

Bystanders who record acts of cruelty without intervening may experience a diffusion of responsibility, assuming that someone else will take action. The presence of a camera can create a psychological distance, causing detachment from reality and a diminished sense of urgency. Additionally, the motivation to capture shocking content for potential online recognition can override the impulse to help. This behaviour reflects a complex interplay between desensitisation to violence and the pursuit of social media validation.[11]

Third Parties Sharing Existing Footage

This may be the most common category and the reason why these videos gain immense attention and go viral within hours.

Those who share existing footage of animal cruelty, despite not being present during the act, might do so with intentions of raising awareness or expressing outrage. However, this can inadvertently contribute to the spread of harmful content, potentially normalising the behaviour and desensitizing the audience. The act of sharing can also be driven by a psychological need to align with social groups or to participate in collective discussions, even when the content is distressing. It is important to recognise that sharing such content can have unintended negative consequences, including fuelling further negative behaviour.[12]

Psychological Drivers Behind Sharing Animal Cruelty Content

Sanam Naran, a counselling psychologist, was interviewed by the NSPCA and highlighted several psychological factors that contribute to the online sharing of animal cruelty videos.[13]

Individuals predisposed to certain personality disorders, childhood trauma, or mental health struggles may be more likely to engage in this behaviour. Additionally, social validation plays a significant role, as individuals seek approval, recognition, or a sense of belonging through engagement on social media.

In some cases, sharing such content provides temporary relief from personal anxieties or serves as a maladaptive coping mechanism. However, regardless of the intent, every share increases the visibility of the original content, inadvertently rewarding the perpetrators with increased engagement.

The Role of Desensitisation in Animal Cruelty

The prevalence of violent and disturbing content on social media has led to widespread desensitisation, where individuals become emotionally numb to cruelty.[14] This phenomenon reduces empathy and decreases the likelihood of intervention. As people are continually exposed to graphic images and videos, their capacity for moral outrage diminishes, making them passive observers rather than active challengers of cruelty. This desensitisation extends beyond animal abuse to other forms of violence, including domestic violence and self-harm, further normalising the encounter of harmful acts in digital spaces.

Influence of Peer Pressure and Group Dynamics

Peer pressure does not only affect adolescents; adults, too, can succumb to social influence when engaging in or witnessing acts of cruelty.[15] Individuals with a history of social exclusion or rejection may be more susceptible to engaging in harmful behaviours to gain acceptance within a group. In settings where animal cruelty occurs collectively, participants – whether active perpetrators or bystanders – may be driven by a need for social validation. The presence of an audience can reinforce harmful actions, as individuals are more likely to conform to group norms rather than challenge unethical behaviour.

Combatting Animal Cruelty on Social Media

To counteract the spread of animal cruelty content online, social media users, organisations, and platforms must adopt proactive measures.[16] Raising awareness through educational campaigns can help shift public perception, emphasising that animal cruelty is both unlawful and morally reprehensible and must not be shared for engagement. Additionally, calling for stricter content moderation protocols on social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram – such as automatically flagging or removing violent content – can limit circulation. However, broader societal discussions about the link between mental health and animal cruelty are essential, as addressing the root causes of these behaviours is key to long-term change.

Conclusion

The disturbing rise of animal cruelty content on social media is a complex issue that demands urgent attention. Whether driven by the pursuit of online fame, social validation, or sheer indifference, the act of filming, sharing, or engaging with such content perpetuates further harm and normalises violence. The psychological effects of desensitisation, group dynamics, and the digital reward system further exacerbate the problem, creating an environment where cruelty can thrive unchecked.

To combat this, a multidimensional approach is needed – one that includes stricter platform regulation, public education, and a sense of ethical responsibility among social media users. By refusing to engage with or share harmful content, reporting violations using the appropriate channels, and promoting compassion over cruelty, progress can be made dismantling this toxic trend. Ultimately, social media should be a tool for positive change, not a stage for suffering.

—

[1] NSPCA. (2024, October 18). R15,000 reward for any information that leads to a successful prosecution [Video]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/NSPCA/videos/1622867721912062.

[2] NSPCA. (2024, October 24). Another stoning; more cruelty [Video]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/NSPCA/videos/517104104505987.

[3] NSPCA. (2028, January 08). Conviction for snake in a bong. National Council of SPCAs. https://nspca.co.za/conviction-for-snake-in-a-bong/.

[4] NSPCA. (2025, January 17). TikTok abuser to face prosecution for force-feeding fish with alcohol. National Council of SPCAs. https://nspca.co.za/tik-tok-abuser-to-face-prosecution-for-force-feeding-fish-with-alcohol/

[5] NSPCA. (2025, January 25). Another victim of social media entertainment. National Council of SPCAs. https://nspca.co.za/another-victim-of-social-media-entertainment/

[6] NSPCA South Africa. (2025, February 10). R20,000 reward for Raygun: Help us find the truth. National Council of SPCAs. https://nspca.co.za/r20000-reward-for-raygun-help-us-find-the-truth/

[7] NSPCA South Africa. (2024, October 18). Brutal killing of zebra highlights horrific cruelty trends. National Council of SPCAs. https://nspca.co.za/brutal-killing-of-zebra-highlights-horrific-cruelty-trends/

[8] Cumming, P. (2023, September 19). Animal cruelty and social media. LifeBonder. https://lifebonder.com/blog/2023/09/19/animal-cruelty-and-social-media/.

[9] n7 above.

[10] n6 above.

[11] Krahé, B., Möller, I., Huesmann, L. R., Kirwil, L., Felber, J., & Berger, A. (2011). Desensitization to media violence: links with habitual media violence exposure, aggressive cognitions, and aggressive behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology, 100(4), 630–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021711.

[12] Wild Welfare. (2023, April 10). Why sharing online animal cruelty content doesn’t help. Wild Welfare. https://wildwelfare.org/sharing-isnt-caring/.

[13] Naran, S. (2025, February 27). Interview by NSPCA.

[14] As above.

[15] n13 above.

[16] n13 above.

Listen to the second episode of NSPCA Today, our brand new animal welfare news podcast, as we delve deeper into this story:

If you are as passionate about animals and their well-being as we are, consider supporting our causes by donating.

Latest News Posts

Will You Be the One Who Takes Action?

Most people will scroll past this. But will you be the one who stands up for animals?

Animal welfare isn’t always in the spotlight, but it changes lives – for every neglected, abused, or suffering animal we help. Our teams work tirelessly, often behind the scenes, ensuring animals across South Africa are protected.

This work is relentless. The challenges are immense. But with more hands, hearts, and resources, we can do even more.

The equation is simple: the more supporters we have, the greater our reach, the stronger our impact.

Be part of the change. Become an NSPCA Project Partner today. From just R50 per month, you can help ensure that no animal suffers in silence.